The In-Between Years

On writing teenagers, and the ache of letting go

I didn’t expect that writing about a teenage boy and his mother would bring me back to one of the most bittersweet seasons of my own life.

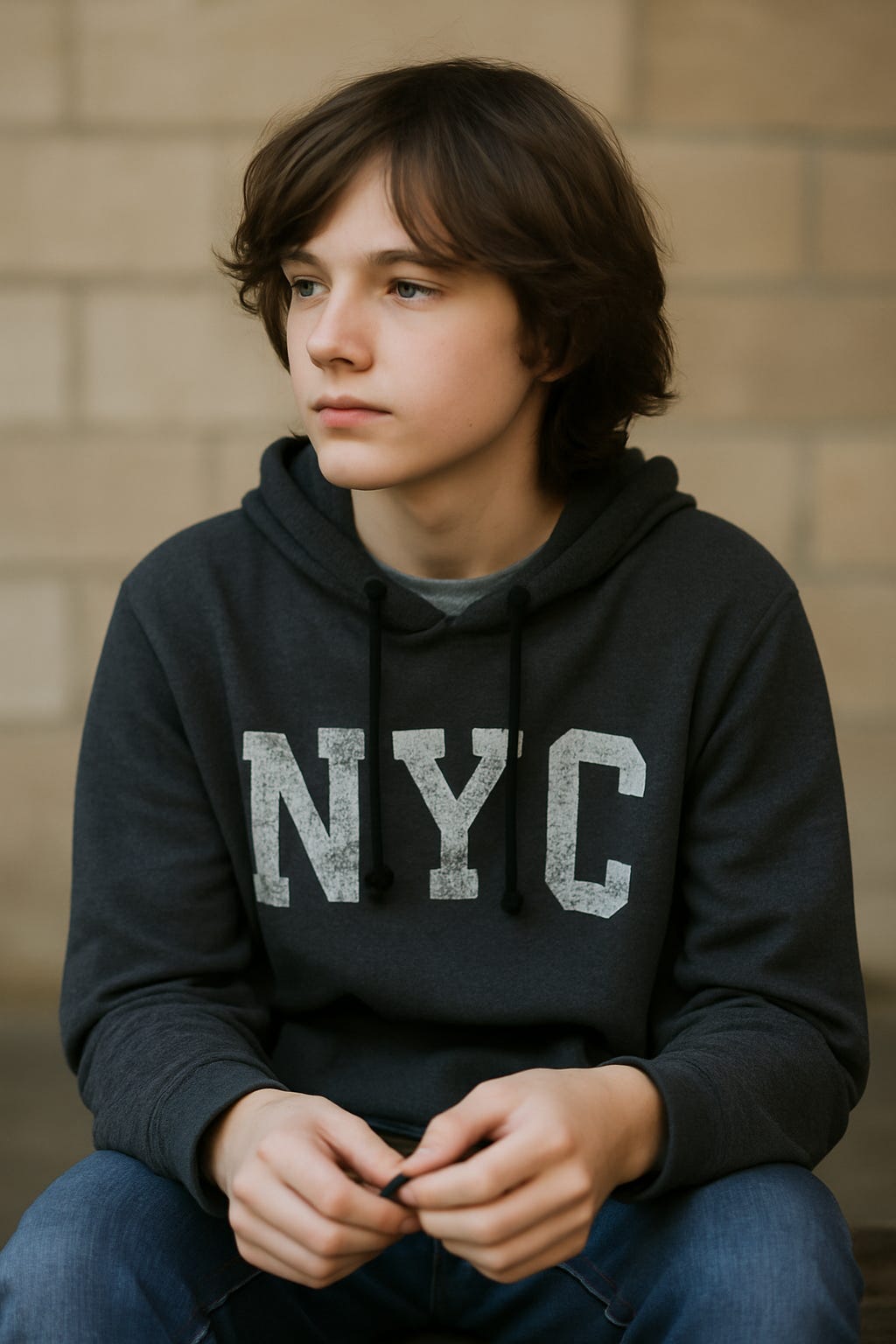

Meet Kez Kerrigan, the protagonist in my dual-timeline novel. He’s seventeen, taking A-levels, teetering between boyhood and adulthood, about to set off for university but not quite ready yet.

And meet his mum, Mary. She knows these days are precious. She doesn’t want to hold on too tightly, but she also knows how hard it will be to let go.

The novel isn’t about this specifically — you could call it a subplot — but as I finished draft three I realised why I loved writing it so much. It’s that liminal space. That moment when, as a parent, you know your child is stepping into a world you can’t follow.

I can still feel those years in my own life. Driving my kids to London with the car full of duvets and mugs, leaving with a lump in my throat. Then visiting them later, stepping into their new worlds. Sleeping in a narrow single bed in halls while my daughter gave up the mattress and made do with the floor. Brushing my teeth in a bathroom with flaking paint and mouldy tiles. One student house even had mice.

And yet — joy. My son cooking me pasta in a pan blackened with age, and it tasted wonderful. My daughter showing me the shortcut to her favourite café. Both of them, beaming with pride, entertaining me, honouring me in their new worlds. The tables turned, and I loved it.

At the same time, there was the ache. The one they call empty-nest syndrome, though that phrase feels too neat for something so messy. Because when it’s exactly what you want — your children thriving, making lives of their own — why does it feel like loss? But it does. It’s a quiet, persistent ache, bittersweet and surprising.

For me — and I know not every parent feels the same — those years of raising my children were the years I felt most alive, most myself, most connected to the universe. That’s why the ache bit so deep. Some parents relish the space, repaint the bedroom, move on. And that’s right for them. But for me, it was different.

That’s why writing Kez and Mary has been such unexpected joy. It’s taken me back to that in-between time when my daughter and son were still at home but already independent, such good company. I was still packing food for trips — hot chocolate and Dundee cake that no one wanted in their muddy festival tent — but they were already stepping out into the world. My son didn’t have the heart to tell me they’d be eating burgers and drinking beer instead.

And here’s the thing I didn’t see at the time: letting go makes space. For them, yes. But for us, too.

My novel ends just as Kez is about to leave, so I’ll never know how Mary handled her empty nest. But I like to think she found her own way, that life opened up for her too. Because that’s the other side of letting go: when we release what we’ve held, something new can arrive.

And now, as my story progresses, I realise before long I’ll have to let Kez go. Trust the book to have its own life in the world, beyond me.

Note: This piece is part of a loose series I’m calling My Novel Year — I’m publishing reflections, research and the small practical steps I take as the novel grows. If you’re following the project, there are other pieces about the story’s origins and structure coming soon.

If you enjoyed this, please tap the heart, leave a word in the comments, or restack — your support helps keep the conversation alive

And if you’re writing about teenagers- I’d love to know how you’re finding dipping into their world- it’s no doubt very different from your own teenage experience. What stands out most?

.👉 I’m Carole — a novelist-in-progress and somatic Life Coach, writing about creativity, change, and the things we carry (and sometimes have to let go). Subscribe for new essays when published. Find out more about my Somatic Life Coaching practice for creatives Here